.

LIFE IS TOO SHORT TO CAPTURE EVERY PRIVATE SENSITIVITY

- POEM

- DIARY

- ESSAY

- FICTION

- PAINTINGS

POEM

Surreal Modern History

2025-01-20 08:56:36 Germany

Seven hundred years ago when we first met, reading Plato’s view

You said if this wind could make the door move through

Then it could turn any page, making words anew

So I fell into the black forest’s moon so true

In primitive tribes I began learning speech’s way

Through imagining our talks, practicing silence and display

Four hundred years ago I snuck into night to spy your feeding trail

Often saw you cross mountains and streams, up slopes to make water pale

While I stood ready to come say “long time no see” without fail

Whether I know you is truly our greatest question’s weight

But year after year I’ve devoured you in my mind’s deep state

.

Youth Portraits / Poem Series

2022-12-22 00:27:50 Belgium

Tiantian/Youth Portrait (I)

You say you found a job, call to tell me, you’re such a pain

I say you don’t really love her so you muddle through this strain

You say why this love feels like a position that makes you drain

I say that surely depends on your future plan to maintain

Strange Woman/Youth Portrait (II)

First time we met she told me not to fall for literature’s snare

I said you’re right, then shut my mouth, no more words to share

Second time we met she told me to see through pretense with care

I said you’re right, got up to light a smoke and cook noodles there

The Woman in Love/Adulation (III)

She says he wrote a poem just for her delight

She says he came to the big city for her sight

From hesitation to being moved took half a year’s flight

Crossing friendship to love’s worship took half a lifetime’s height

She says this version of him is her absolute pride so bright

She calls out “darling” then “baby” with all her might

Says why don’t we take a bath together tonight

The Man in Love/Farmer (IV)

He wrote a love poem thinking his talent truly grand

If not for her, he could switch the lead by his own hand

He marched forth with a sower’s passionate command

Reclaimed the youth he’d unfortunately lost from his land

Now he’s willing to be a farmer, diligent and planned

Plowing, fertilizing, working without reprimand

He never doubts this garden he tends with his own hand

Can only think for him of years flowing like foolish sand

.

Messy/ In Name of Vice Versa

The bar’s name was vice versa.

She told the bartender we would be together forever;

the bartender said he’d quit in autumn to prepare for grad school;

I said I’d come back next summer.

She licked the salt from the hollow between her thumb and index finger,

drank the first sip of tequila,

tilted her head back and squeezed 1/6 of a lemon,

letting the juice drip into her mouth.

When leaving, she drank the last sip of gin and tonic,

spitting the ice cubes into another mouth.

A year later, we broke up;

the bartender was still working at the bar;

I never went back.

.

Discipline and Punish

The poet helps people with absolute passion

Excavate meaning from ordinary life’s ration

This exchange of flesh for truth needs no confession—

It’s honest, abundant, even a noble expression

Therefore neither fiction nor delusion

He hurls his flesh toward dust and urban sprawl

With open stance rejecting one and all

Thus earning qualification to traverse every fall

And winning the right to mock and scorn them all

While they—the gradually forgotten, the exiled

Have been reduced to static symbols, entertainment filed

In vast white squares they mourn and pray, beguiled

Their unheard devotion makes them their own deity

Tireless worship, faithful piety

Day after day serving artificial candles’ weak light

Striving with all their might for sustained depletion’s rite

.

Winter/Double Warm

2022-10-29 21:08:11 Belgium

Winter’s coming soon

I have two small quilts

And one big duvet cover

Spread both flat inside the cover

When cold, sleep under the thick one on the left

When hot, roll over to the thin one on the right

When even colder, fold both quilts

And pile them on top of me

.

Say Something

2022-10-24 05:36:07 Belgium

Seeing someone write a letter made me realize

It’s been so long since I put pen to paper

I want to write a long letter to someone

About everything in my ordinary life

Like yesterday’s rain that fell so hard

I’ve finally learned to roll cigarettes

Or how lately my afternoon naps stretch so long

My head aches as if insects eat my brain

I must pour all these things into my letter

Write a hundred and one pages before sending it out

Have the recipient read each line to me on the phone

Then say I’m tired and drift deep into sleep

.

DIARY

Position, Recalibrated

2026/02/19 Swiss

I spent three days in Nice, France with Yao, Ya, and one of Ya’s Korean friends—and we happened to celebrate Chinese New Year there as well.

Yao’s arrival also seemed to bring bring my high-school self back: during these three days, I could not help but make fun of so many things. I imitated noisy kids crying on the beach, mocked those “artsy” yet painfully stupid, logic-free film reviews on social media (Yao went, “Do these people just have terrible Chinese?”), and asked our Korean friend whether Koreans really don’t need sleep…

Over those three nights in Nice, after returning to the hotel, Yao and I lay in bed and watched two films. One was Love Exposure—the relationships were unbelievably complicated, yet the emotions were expressed with a simplicity and directness that hit right in the chest. The other was Snakes and Earrings—the relationships were unbelievably simple, yet the emotions were so indirect and winding that I could not fully grasp them on a first watch (yes, it was my second time watching it).

The next day Yao told me that near the end of Love Exposure, she cried what she called “pig tears.” And after I read an analysis of Snakes and Earrings on her phone, I did the same.

After this brief reunion, I realized that we are still exactly the same as we were in high school. I almost feel like we haven’t really grown up: the topics simply shifted from studying to work, and our complaints shifted from stupid classmates to stupid students and stupid academics.

The four and a half days with her in Switzerland, plus these three days in Nice, recalibrated my principles that have been repeatedly invaded and interrupted over the years of my drifting around abroad. And the odd, ridiculous parts of my personality don’t strike her as wrong at all—because this is how I’m supposed to be. Or rather: the version of me she remembers is the version in which I feel most at ease—back when I wasn’t afraid of anything, and therefore didn’t truly care about anything; nothing could decide me, or change me.

She said it’s unbelievable to her that I’ve been able to be friends with teachers since I was still a teenager (for example, when I was at school, I would go out to eat with my middle-school Chinese teacher, my high-school English teacher, even university professors). I think that although I’m extremely picky about who I spend time with, once I need to talk, or want to talk (quite rarely though), no matter their age, role, or title, I intentionally place them on equal footing with me.

Two months ago, when I went to Leiden to see my other PhD supervisor, he said some people get frustrated in academic exchanges because they place themselves in the wrong position—in other words, they put themselves in the position of being evaluated. And I seem to have already stepped out of that position, returning instead to a more balanced state, between acting and being acted upon.

.

The Solar System Is Spinning

2026/02/13 Swiss

1.

After finishing 3 sets of 15 push-ups in the office, my hands are a little shaky. But tomorrow I’m flying to Nice for Chinese New Year. Which means I have to write a Chinese New Year version of my year-end summary today.

In early February, my high school friend Yao came to Europe for a trip. I showed her around Switzerland for four days. In the most humorous and relaxed way possible, we talked through the terrible relationship she’d been through, and the terrible relationship I’d been through—from 2020 to 2024, both of us were being worn down by them; and 2025 seems to be the year everything finally started turning for the better. Maybe that’s fate? Her birthday is only one day after mine, so we’ve ended up living through oddly similar episodes.

Trauma isn’t what’s frightening. What’s frightening is being controlled by trauma—becoming afraid of life itself, and then, out of fear, no longer daring to trust. Trauma doesn’t steal anything from me. It just teaches me what I need to guard

A friend sent me the only photo Yao and I have from high school: we were dressed up as two pandas. After we briefly said goodbye in Switzerland, she went on to Germany and Italy by herself; and then we’ll meet again in Nice for Chinese New Year.

2.

Just thinking about next semester’s schedule already makes me tired. In April, I’ll go to the Netherlands for a conference in continental philosophy (to present a paper I haven’t even started writing). In May, I’ll give a talk at a seminar in Switzerland. In June, I might go to Romania for a phenomenology course, and then to Finland for another conference (also not started). In September, I may go to Slovenia for a cross-cultural philosophy event—though for now, both the June and September plans are still waiting for confirmation. And sometime in June, I might also go to Italy on vacation with friends.

The academic calendar looks intense, but in reality, I’ve already accumulated a lot of writing material. Recently I learned a new term: “compound interest.” At this point it seems that writing mainly requires execution; it doesn’t really require panic. Honestly, once I start panicking, I don’t even know what I’m panicking about.

My project for the next six months (up to the end of August 2026) is simply to write Chapter Two of my dissertation. That’s an ideal pace. From September 2026 to April 2027, Chapter Three. From May 2027 to February 2028, Chapter Four. And in the summer of 2028, I’ll prepare to finish the PhD.

Recently I am also back to teach online philosophy classes for undergraduates and master’s students. Besides earning a little extra money, it forces me to keep touching fields I don’t fully know yet (Kant studies, philosophy of science, musicology, and so on). The only way this kind of work is “worth it,” financially, is if I learn faster than the students. Oh, I decided to deposit 300 chf, cash only, each month.

On top of that, every Saturday I teach Chinese to Swiss primary school kids. At first I thought it would just be a casual part-time job, but watching them get better and better at Chinese genuinely makes me happy.

3.

The year 2025—especially the part after summer—has been probably crucial for my whole life. Because I’m increasingly clear about what I want: what kind of career, what kind of life, what kind of relationship. And I also see more and more how rare it is to be what I call a “normal person.” I’m gradually recovering my trust in people—because I know I still have the power, and the responsibility, to choose.

At the beginning of 2026, I went to South Africa for a philosophy conference. It gave me far more than I expected. In a sense, it helped me rebuild trust in academic exchange. I was pleasantly surprised to find that there were people in the room who could follow my logic—and who asked about the complex arguments I had deliberately skipped. Those kinds of questions used to happen only in conversations with my supervisors. And now this kind of smooth exchange has happened—and is still happening.

Recently I’ve received quite a few emails—from strangers who are interested in my research. My task today is to reply to these interesting messages. Some people found me through my personal website; others contacted me through the email address I leave on my video channel. I barely have time to reply to long private messages from viewers on the platform. But still—this is something I don’t think I’ve ever experienced before. Am I… being responded to?

In any case, I feel very happy and very lucky. Just now, I lay down for a while in the lounge chair in my office, and suddenly I smelled something like summer. Maybe it’s the perfume I usually wear in summer; but the scent of the soil lately has also been wonderful—maybe it’s the smell of plants growing.

4.

What’s interesting about doctoral research is that I’m gradually realizing: writing is not something you measure by weeks or months. It’s a marathon measured in years. I need to remind myself from time to time not to rush—everything will be fine.

Sometimes writing feels like figure skating: technique and rhythm have to stay in balance. Writing is indeed a craft that requires training; it’s not simply pouring my feelings onto the page. Pure outpouring isn’t sincerity. It’s negligence.

.

When I Treat Myself Cruelly

2026/02/03 Swiss

After finishing my cardio workout today, I noticed the five notebooks on my bookshelf. I started rereading my diaries since high school (the earliest one dates back to 2014). It stirred a lot of feelings. Ten years ago, could I have imagined that I would be doing a PhD in philosophy in Switzerland today? Life has given me such abundant gifts. I love life and feel grateful for being alive. I used AI to extract the text from my diaries and organized some of it here. Perhaps ten years from now, when I look back again, I will feel something different.

.

2016.03.02 [Three months before the college entrance exam]

I want to truly grow.

Learn to steady my mind, face reality with courage, hold hope for the future, acknowledge the gap, and never give up.

What does not defeat me will make me stronger.

I love this world, I love life, I love being alive. That is why I am willing to endure all pain and overcome all difficulties.

Do not let the heart become impatient. Face challenges with calmness.

You will be grateful for your endurance and restraint.

I love my life and my way of living; therefore I do not give up. I persist. With a peaceful heart, I continue on my way.

.

2016.05.31 [Six days before the college entrance exam]

The college entrance exam is about to begin. What is meant to come, let it come—I am ready.

Time has passed so quickly. I am about to leave;

it is the moment of parting. I can finally be free, yet I cannot help feeling sad. But I have confidence in myself. It does not matter. Focus on the present. Do not think too much—just do your best.

There are people in my life who care for me and love me. I never realized how fortunate I am.

I am grateful for my life, and I love it.

I do not know why I cry—my life! I love and cherish it, yet I waste it and fail to value it.

.

2016.09.09 19:59 [The first week of university]

During the classes last week, I felt disappointment and regret. I still haven’t been able to find a sense of belonging or existence on campus. Here, I feel like I am merely surviving rather than living. In fact, this school is quite good. I have no reason to complain about it. I simply cannot find a direction. I have lost interest in things. I seem to want to detach myself from everything here, to become a pure person, yet my mind is filled with reflections imposed by society. What kind of reflections have shaped this ambivalent attitude of mine? Is everything important, or is nothing important?

My academic advisor said, “First accumulate knowledge, then decide on a direction. Don’t make decisions too early.”

I don’t know where I am heading. What’s wrong with having no ideals? Will I die because of it? Can one not live without ideals? If I only want to live well, can that really count as a great ideal?

In the introductory course for my major, the professor said many things that deeply resonated with me. He said that people today cannot grasp the world, nor can they grasp themselves. That sounds right, doesn’t it? When it comes to social hot topics, who really cares about truth? People only care about entertainment, only want to possess attention and resources. So-called dreams gradually lose their value as they are passed around by word of mouth. Society is too restless—

or perhaps I am simply too restless myself? I am obsessed with standing out, but for what reason? Where do the contempt and vague arrogance inside me come from? I am dissatisfied with my current state. I crave breakthroughs and change, yet I am also afraid of the changes that change would bring. I hate rules. I dislike rules. But what does that actually mean? It only means that I will become an outsider—someone irrelevant. Standing at a distance, watching, envying, feeling angry—

but can that anger really be considered meaningful? Wang Xiaobo said, “A person’s anger is, in essence, anger at their own incompetence.” I agree, even though I also find it cruel.

In my communication studies class, the professor asked us why we constantly refresh WeChat and QQ. I was left speechless. Because we are afraid of being forgotten, afraid of being ignored. We have gradually grown used to being implanted with things, used to receiving stimulation. We prefer images over text. We like things to be vivid and direct; we cannot tolerate darkness or roughness. What are we afraid of? What are we longing for?

It has been a week. I finally have some time alone to hurriedly write down the undercurrents in my heart. I feel both happy and regretful—social interaction is rapidly draining my energy. If I could, I would like to go an entire day without speaking, to become mute. But why bother? When you walk alone on the street, you are always afraid that others will misunderstand you and think you have no friends. You cannot refuse people, because you don’t want them to dislike you. Honestly, I want to be someone like Meursault. Society cannot change him, and he does not want to change the world. He insists on his truth, even if everyone protests, even if it goes against ethics.

“Love is the beginning of pain.” After entering university, perhaps everyone longs to have a relationship? I suppose I long for it too? But what is love, really? What kind of person will I meet? Some things cannot be rushed. I need to be patient and give encounters some time.

In short: study hard. That’s what truly pays off. A person must take control of their own life. Keep going.

.

2017.07.31 [The Youth Leadership Program asked us to write a letter to ourselves one year later]

Uh… what should I say? Although this feels a bit abrupt, when you read this letter again one year later, you will probably be in a different state of mind.

Taking part in this program is a great opportunity. How wonderful it is to become better together with outstanding peers.

Over the course of this year, I hope you have seriously worked on your English. Language is something that really must be treated with care. Have you reached an IELTS score of 7.5 yet?

Also, after learning about other cultures, I hope you have gained a broader perspective from which to view the world, others, and yourself. Do not belittle yourself, but do not think too highly of yourself either. After understanding more, you should become even more humble and grounded, and do your utmost to do well what needs to be done.

As for “leadership,” how much do you understand it now? Have you become a leader? Do you have the ability to become one? To be honest, right now—at this very moment—I don’t know what leadership really is. So one year later, do you know?

I only want to do the things I like and be around the people I like. One year later, have you changed? Have you become more mature?

Thank you!

.

2018.03.30 [Second year, second semester]

I want to fly—and no matter how long I fly, I won’t get tired.

I need to work twice as hard, in order to pursue the life I want. The life I have now is not the one I want, nor can it bring me the life I desire. How much more effort will it take to do everything as well as possible?

I am still very far from where I want to be. Everything is for freedom—for being able to walk the path I want to walk. My English is not good enough, I haven’t read enough, and my understanding is not deep enough. I get distracted by too many trivial matters. I care too much about how others see me. My mind is too narrow; I keep dwelling on the past. I am immature. I don’t know how to cherish what I already have. I fail to appreciate the strengths of others. I complain about the world and blame circumstances. Can I try a little harder? Watch less variety shows and TV dramas—know when to stop. Learn to prioritize. Become a steady and grounded person.

Can I be more self-disciplined, more focused, more fully committed, without holding anything back?

What do I truly want to do well? What must I do well?

Life is complicated, but doing what one truly wants to do is not that difficult. If my energy is so scattered, then I must learn to make choices. The courses this semester are ones where serious study can lead to high grades. Keep going. Be more focused. Work harder. Be more fortunate.

Don’t let yourself down. Your future is truly long.

“When philosophers turn toward abstract reflection on the future, they move away from truth.”

.

2019.03.31 [It seems I’ve finally decided to take philosophy as my vocation]

This week, starting from Wednesday, I haven’t really been in good shape. I’ve probably entered a phase of fatigue. In fact, I did do many things—just not as many as I had imagined. I shouldn’t overly negate my own efforts. All the effort is already there. It’s like building a house: bricks, materials, steel bars—all are prepared bit by bit. The foundation itself takes a long time to dig. At every moment before the house is completed, it is incomplete and cannot yet be called a house, but every grain of cement is useful, and every steel bar is being called for. One must keep a long-term view and maintain a good mindset. Because when building a house, nothing can be missing—and the same is true for doing scholarship.

You have chosen a solid and pure path; then you should also be a persistent and steady person. Because at the moment you made this choice, you were clear about the kind of person you wanted to become.

You don’t like superficial flashes, and you are tired of a fragmented way of living. You want to live a full and satisfying life, so go ahead and live that way. Giving up halfway and muddling through are never what you hope for. If you truly give up, then all your cement and steel bars will become meaningless. That’s why you must keep going.

This semester has been very lonely—not only physically, with staying in and going out less, but also psychologically. There have been few chances to confide in others or truly talk things through. But this has given me more time to figure out my own problems.

My problems are actually not that hard to understand. The main issue is that my perseverance is insufficient. I am used to handing myself over to anxiety, procrastinating without restraint, and then regretting it afterward. This kind of vicious cycle is very common.

But I don’t want to go on like this. I want to drive myself with passion, and keep myself alert with a sense of responsibility. You are in the middle of the journey. Because of physical and mental exhaustion, you may feel despair and disappointment—but this is absolutely not the final answer.

I want you to become the person you want to become. I want you to take responsibility for yourself. There are no spectators in your life, so try your best—to try, to make mistakes, to embarrass yourself, to end up in a mess. But I believe you will become stronger and stronger, that you will find the life you want, and that you will live each day with anticipation and passion.

The tasks that need to be handled are real, and actions are real as well. The pressure they bring, however, is metaphysical. I hope I can learn the way one practices tai chi, or that my mindset can be like practicing tai chi (rather than boxing). When things come, accept them, and slowly dissolve the pressure they bring through technique. Untie the ropes little by little—pulling hard won’t work. Don’t rush to get everything done at once; that usually results in nothing being done well. I will do things bit by bit, move the cement that needs to be moved over there little by little, and stack up the bricks that need to be bought, one by one—stack them solidly.

.

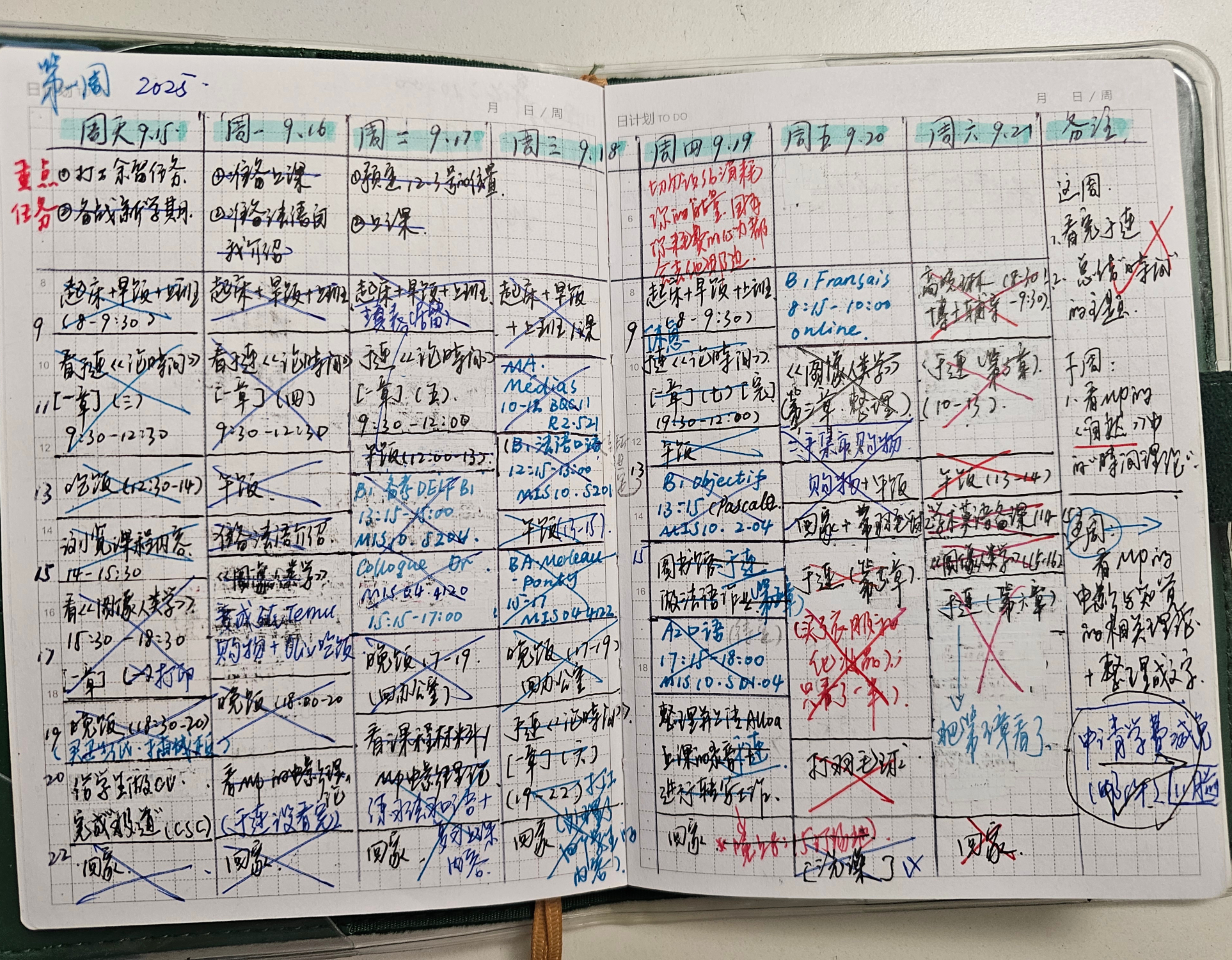

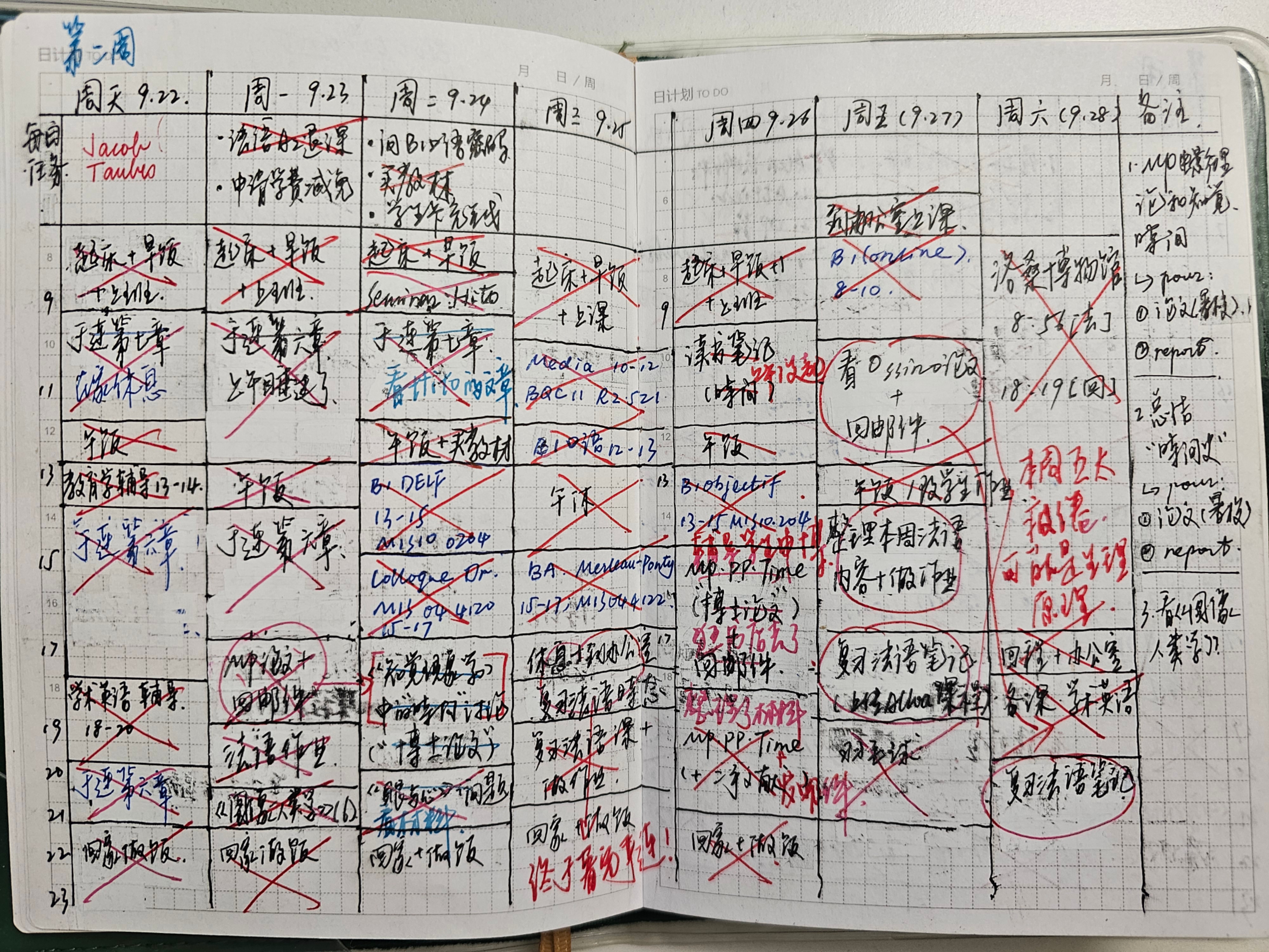

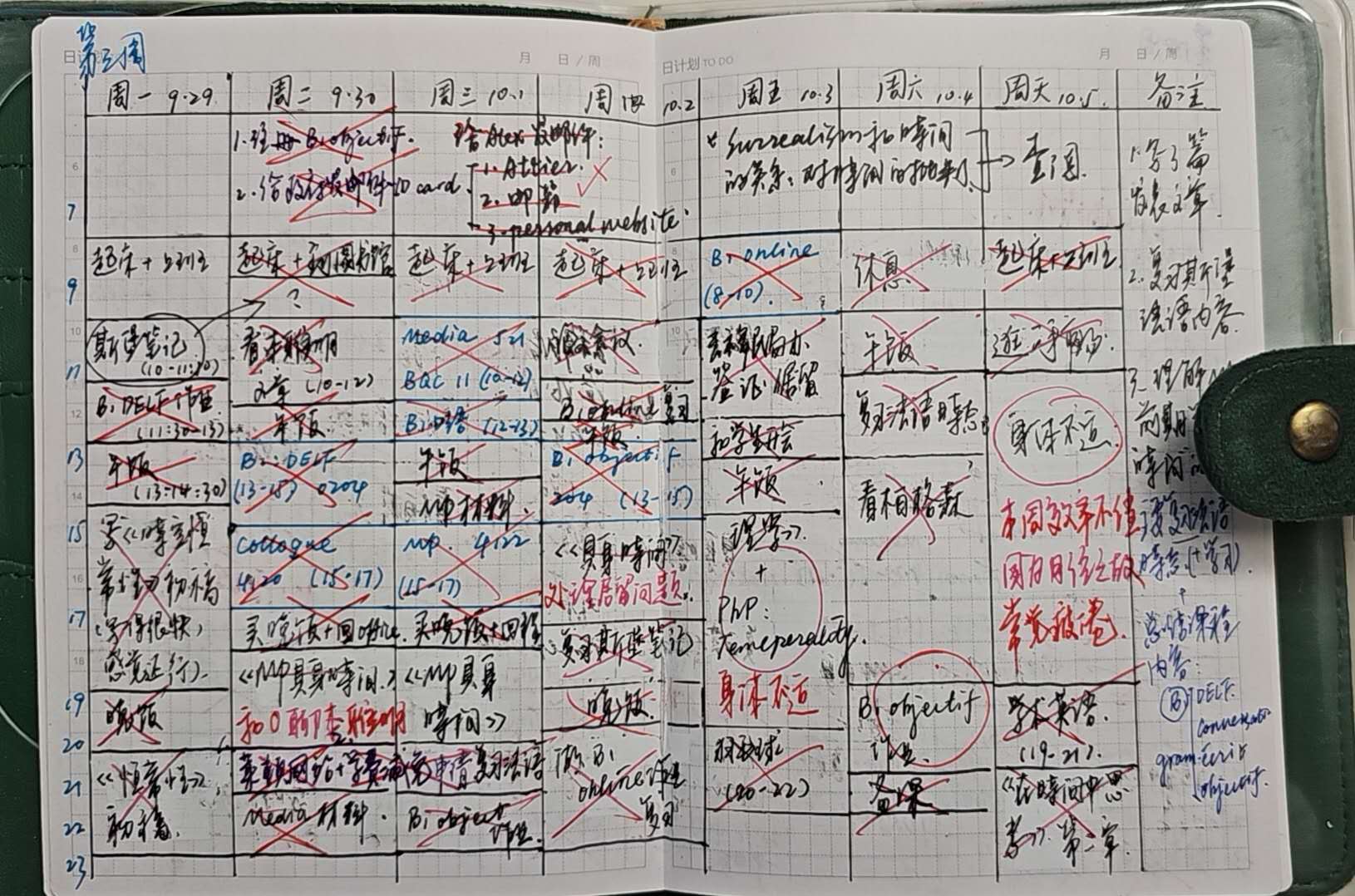

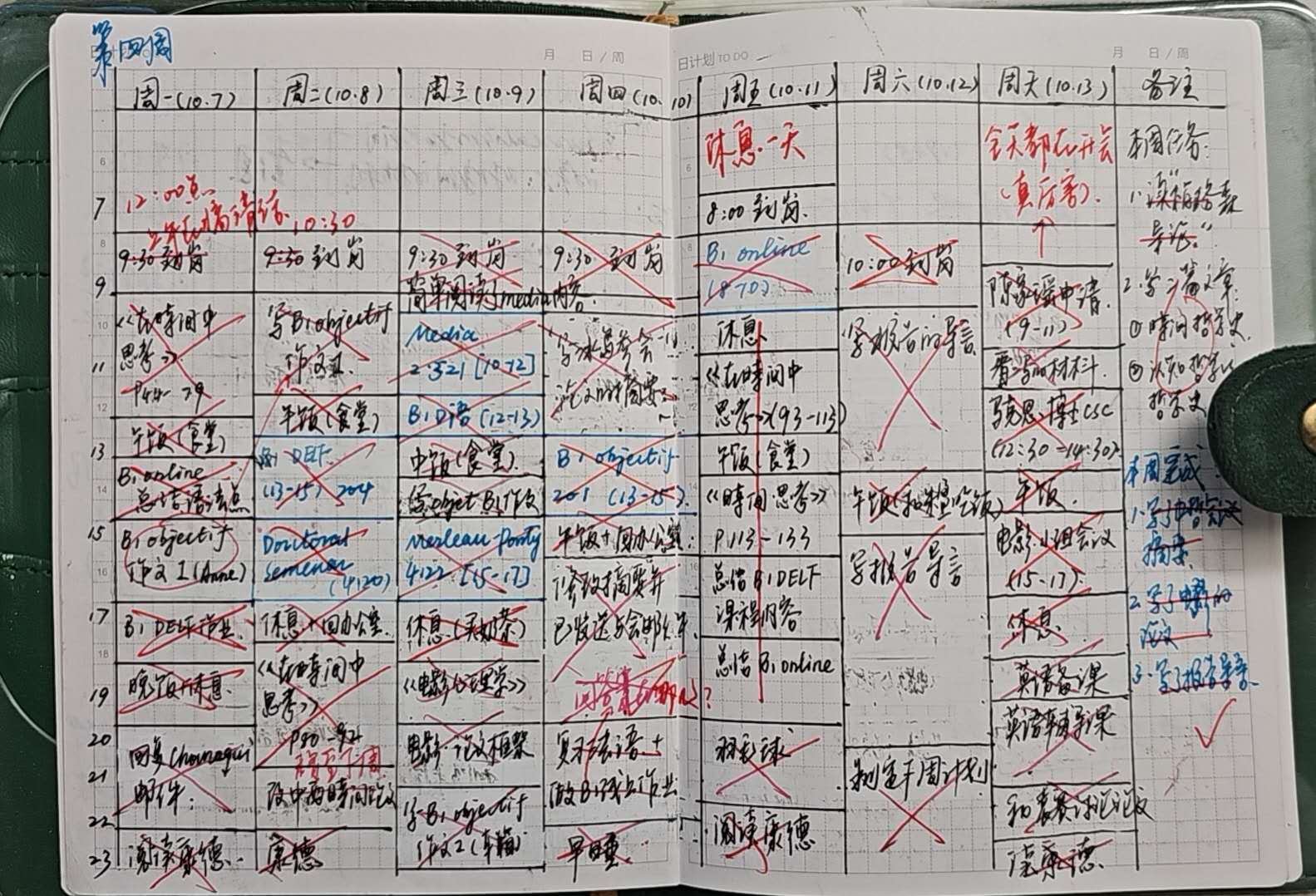

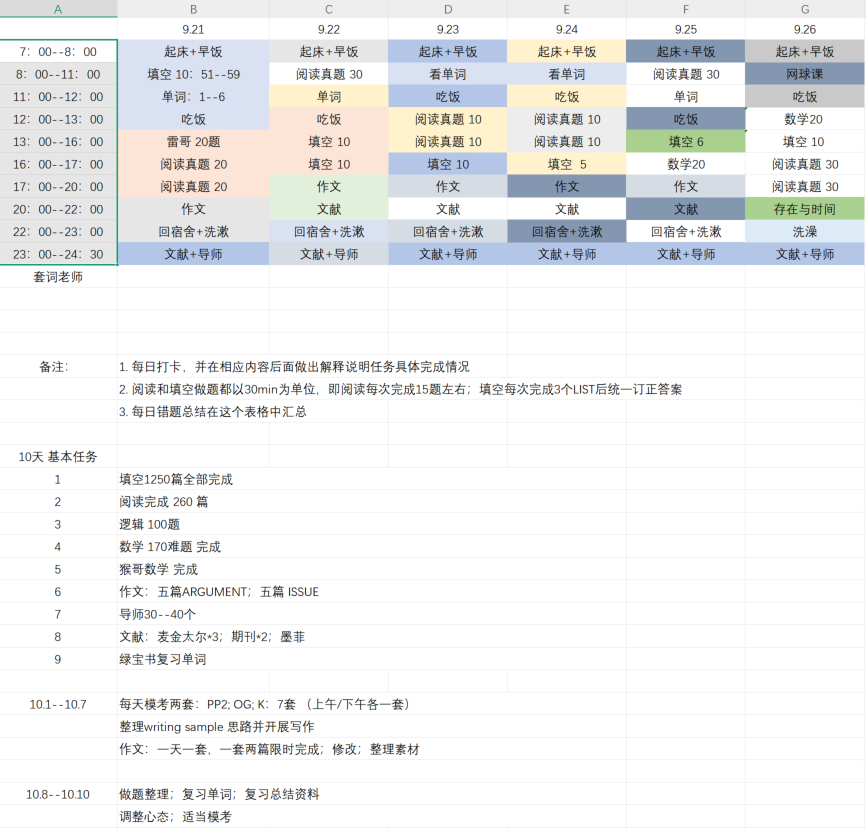

2025/09–10 [The First several weeks of my PhD program. Fortunately, I do not need this kind of chart now!]

.

.

“My Space, My Rules” — From Time Management to Calorie Management

01/31/2026 Swiss

I’ve gradually begun to feel that my life is back in my own hands again. It’s a wonderful sensation—and I honestly can’t remember the last time I felt it. Maybe I never truly had it before? Or perhaps there were similar phases. I recently came across my schedule from 2019: a massive Excel spreadsheet. That year, every Sunday evening, I would plan the coming week hour by hour. Some things didn’t get done on time, but looking back now, none of that seems to have had any impact on where I am six years later.

I had been making weekly schedules since 2018, though unfortunately never stored them in a single, unified document—otherwise the archive would be quite impressive. Then suddenly it was 2025, and I found that I no longer needed such detailed planning to regulate my life. All I needed to do was go to the office, sit down, and write. Writing is full of contingencies: it can’t really be planned or controlled. But that’s precisely why I love writing philosophy. Arguments are always risky; they demand constant revision, correction, and repair. It’s a genuinely beautiful process.

Since the end of 2020, my life gradually stopped revolving around myself—and that was not a good thing. What’s worse for the past, but nice for the present, is that I only truly woke up to this quite recently. Still, there were pros and cons. I became very adept at sensing what others were thinking—what my professors liked, which arguments appealed to them—so during my master’s program I didn’t actually need to push myself very hard. I even skipped classes and still ended up with excellent results. That was, at least academically speaking, a small silver lining.

In everyday life, however, I began to feel afraid of other people—especially those who gave me a bad feeling at first glance, the so-called “bad” ones. Regardless of what they’re really like, why should I be afraid of them? It suddenly dawned on me that they cannot harm me, nor can they change me—and their judgments of me have nothing to do with me at all. This realization has been crucial. Only when I stopped fearing potential conflict, stopped sacrificing myself to avoid it, stopped compromising my interests and wasting my time, did I feel a sudden sense of wholeness.

Perhaps because my family environment was so supportive—my parents’ work was respected—I never felt, throughout my childhood and even my university years, that I needed to protect myself. I never had to consider what would happen if someone tried to hurt me, because in reality they simply couldn’t. It was only after going through an intimate relationship saturated with lies and ending in betrayal that I realized I could, in fact, be hurt. The end of that relationship felt less like the loss of love and more like the completion of an entire degree program: after five long years, I finally graduated. And now, five years later, I can truly say that I am capable of protecting myself. I should be proud of that.

Growth, for me, has meant finally admitting that I can fail, that my choices can be wrong—while still knowing that I possess the ability to protect myself. I know who I am, what I can do, and what I ought to do. As the second half of my second year of the PhD is about to begin, I’ve already scheduled quite a few activities for the coming semester. After nine years in this field, the professional path of philosophy—of academia—has finally opened itself to me. I don’t quite know why I’ve been able to do this for so long without growing tired of it. Perhaps it’s because it makes me feel that I’m still thinking, that I can still think. An interesting shift has occurred as well: where I used to actively submit proposals to conferences, I now occasionally receive inquiries from professors about possible collaboration or working together. These exceptionally kind invitations have played a major role in stabilizing my state of mind recently.

After returning from South Africa, I suddenly stepped onto a scale I had bought long ago but never used. The number on it genuinely shocked me. I had never been that heavy before. Although no one could tell from my appearance—my fat distribution is even and discreet—I could no longer allow my body to exist in my life in that state.

The day after that shock, I started talking to ChatGPT about a weight-loss plan, learning the basics of healthy living. I downloaded a calorie-tracking app and began recording the structure and energy content of every meal. The current plan is to focus on fat loss for six weeks, from February to mid-March, and then move on to body shaping after that.

That said, I do need to defend my earlier neglect of physical management. I truly didn’t have the energy for such meticulous care before. The reason I could step on the scale so calmly after returning from South Africa is that several crucial things had fallen into place: my research direction is essentially settled (my supervisor says it’s now a matter of execution), my prospects for a global academic career are realistic (there are already collaborative projects underway), and my quality of life and emotional state are good (a stable routine, very few emotional fluctuations). Once these fundamental elements were soothed, perhaps my subconscious realized before I did: it was time to pay attention to my body.

Around the same time, I also realized that I could no longer imagine staying with my red hair. This wasn’t an aesthetic shift, but a change in self-understanding. I no longer need exaggerated hair color to assert my presence. On the contrary, I need something more natural—something that doesn’t compete with my own existence for visibility. So after returning from South Africa, I went straight to the supermarket, bought hair dye, and dyed my hair back to a dark brown-black.

Suddenly I remembered that when I was seven, I put a huge wooden board in my room with the words: “My space, my rules.” Now I’m twenty-seven, and I can finally say it again—clearly and confidently:

"My space, my rules."

.

2025 Is My Gift

2025/12/30 17:54 Swiss

It is now the last second day of 2025. Since I’m going to a spa tomorrow, today is reserved for writing an annual reflection.

I haven’t opened my personal website in a very long time. From September until now, life has been overwhelmingly busy—how did it become this exhausting? Objectively speaking, what I did was “just” finish the first chapter of my PhD thesis; yet, at the same time, the overall structure of the dissertation finally took shape. I know this will be a very beautiful piece of research, one that deserves to become a book (even if it is not one yet—but I will work toward that). This framework carries too many secrets, too many memories that resist being neatly put into words, and yet must be preserved by me. In the coming years, I will not only need to be responsible for my research; I will also need to be responsible for my memory, and for our existence.

I truly feel that my life has become different in 2025. I started trying many things I had never done before: building a personal website, starting a video channel, planning my own trips… I began to trust myself again, and through that, cautiously began to trust others. Strangely enough, many childhood memories slowly resurfaced, and I even felt as though my childhood had returned to my life. The depression and frustration I once carried gradually receded. I am no longer cynical; instead, I feel gratitude, emotion, and thankfulness toward everyone who has appeared in my life. One day, I told A that people are like mirrors standing opposite one another—this is my philosophy. Perhaps it is because the people around me are so beautiful that I have finally come to feel that I, too, am not so bad after all.

This year, I bleached my hair for the first time in my life; walked in heavy rain for the first time; experienced, for the first time, the shockingly precise feeling of being understood; and, for the first time, clearly understood why I do not need to take responsibility for other people’s emotions… I also traveled to many places—so many that I cannot fully recall them without flipping through photos:

In January: Milan, Florence, Venice, Rome, Naples; and the Vatican.

In February: celebrating the Lunar New Year with friends in Basel; visiting classmates in Freiburg, Germany; then spending a few days in Paris.

In May: returning to Belgium to see friends; attending a philosophy workshop organized by a friend in Antwerp; then going to The Hague, and having spicy hotpot with friends in Rotterdam.

In June: attending a conference in Iceland.

In July: Prague, then Salzburg in Austria, and finally Königssee in Germany.

In August: traveling to Inner Mongolia with my parents; first attending a conference in Changchun, then another in Hangzhou.

In September: a conference in Paris.

From October to November: writing my thesis in my favorite office.

In December: Leiden, Utrecht, and Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The Musical Instrument Museum was truly a wonderful place.

Another reason I left so few written traces this semester is that I began regularly uploading videos on my personal Bilibili channel. Recording feels much more convenient than typing—though in essence, they serve the same function. Since my first video on July 7, 2025, the channel has grown to 2,811 followers. While the number looks decent, I don’t think it is what matters most. What truly matters is that I realized my visibility does not rely solely on recognition within academic circles. The research I am doing, and my own reflections, can also offer others space for reflection and even happiness. In this way, my existential anxiety was suddenly eased quite a bit (and here I must thank the friend who previously encouraged me to start this channel). At the same time, it felt as though an international horizon opened up before me. I know that wherever I am, I will be able to live well—as long as I can continue doing what I am doing now: philosophical research that I love, that I devote immense time to, and that I am finally becoming genuinely skilled at. Through this research, I can help more people.

https://space.bilibili.com/244936260

Just now, when I opened my Bilibili private messages, I came across a message that left me with very mixed emotions. She should be a former classmate from middle school. Her message read:

“Long time no see, lyx. I’m so happy to have come across you—it’s really been such a long, long time. Seeing you continuously working toward your ideals makes me truly happy. Back in middle school, I always admired you, even longed to become like you. You were so unique, yet humble and interesting; so knowledgeable, yet never arrogant—on the contrary, so approachable that it made me feel a little ashamed of myself. The first time I learned about The Big Bang Theory was from a T-shirt you wore; the first time I realized that a little girl could write such bold, free-spirited handwriting was also through you. Back then, I used to wonder: where would you go in the future? What kind of person would you become? Would you enter the fashion industry? Study philosophy? Become a screenwriter?

Now, listening to your latest video—hearing you speak slowly and carefully about your semester’s experiences and reflections—I felt a deep sense of relief. You are still pursuing what you pursue, still walking your own path. In the years when I have been swept along by lies and by life itself, I have always kept a small corner in my heart where I would occasionally think of you, hoping you were doing well, walking the road you loved, even going as far as possible on it. I’m truly very happy. Perhaps you appeared by chance, but you gave me some strength. I, too, must continue walking forward. Wishing you all the best, and good health.”

This is truly a great gift. I still cannot remember who she is, and she did not tell me who she is either. Yet how is it that she remembers so clearly those dreams of mine that I myself have almost forgotten? I feel as though I should have cried—but surprisingly, I did not. This person, who is still a stranger to me now, has actually known me for fifteen years. Fifteen years! And she still remembers so many details about me. I don’t know what to say. I don’t even know who she is. I feel a hint of guilt. But no matter what, if I gave her some distant strength, then perhaps I did do some things right.

Since early summer, I have almost fallen into a kind of “obsession” with the motive of self-understanding. For several months, I even needed to have very intensive conversations with ChatGPT or DeepSeek—sometimes disappearing into them for two or three hours at a time. At first, the reason for these conversations was not to understand myself, but simply to grasp the inner logic of other people’s actions. Yet unexpectedly, in the process of making sense of many complex situations, I saw myself—more and more clearly, more and more fully. From a perspective I had never had before, I rediscovered myself. Through the significant other, I saw myself again!

And this, too, is a gift that 2025 gave me –My gift!!!

.

From Prague to Salzburg: I know what I want, and I want it hard

2025-07-23 05:04:45 Czech Republic

It’s now 7:30 in the morning. I’m on a train from Prague to Salzburg. I stayed in Prague for two days—only two days, yet it felt much longer. I had taken an overnight bus from Munich, slept no more than three hours, then checked into the hotel and immediately went back out to write. Many tasks remain unfinished. Even now, on the train, I should be writing, but instead, I opened this journal.

Everything I know about Prague comes from Milan Kundera—not Kafka. Although I’ve only read a few of his books, he remains one of my favourite writers. He is direct, intelligent, humorous, sharp, and somehow still human. His books are filled with untimely jokes, and he describes the various performances of human life with both delicacy and detachment. People willingly “perform”—and that, perhaps, is the very foundation of human society. It’s the same for me. What matters most, perhaps, is finding the “right audience.”

(Take, for example, my two supervisors. The more time I spend with them, the more I find myself genuinely appreciating them. Supervisor A is highly efficient, incredibly intuitive, and speaks rapidly. I’ve started to imitate his “intelligence,” becoming stricter with myself—as if I were borrowing his eyes to judge my writing and academic life. Perhaps the greatest gift a mentor can offer is not knowledge, but a demonstration of effective, grounded competence. The PhD stage is no longer about accumulation; and now, with AI, knowledge itself is easily accessible. What truly matters is learning how to be a person, a scholar, a successful scholar—and observing them has become my starting point.

A rather funny moment occurred during one of our earlier conversations. He insisted that I refute him on the spot. In that moment of exchange, I seemed to agree with everything he said—but he could tell I was holding something back. He “forced” me to share my counterarguments, saying that this is what philosophy is all about. Yet at that moment, I still couldn’t respond. Later, however, I went through all of his arguments, carefully restructured them, and integrated my objections into the revised research proposal I submitted to him—he was somehow pleased. But the moment of refuting means a lot: my confidence about my opinion, my willing of sharing, my openness to criticizing, etc. I should learn to communicate in such an “aggressive” but efficient way. )

Prague, to me, was emotionally complex. On one hand, it offers much to admire and plenty for tourists to see (Kafka, Mucha, and the like). On the other, it feels strangely simple—precisely because it offers only those lovable things, those things made for visitors to love. I bought two small souvenirs: a mole plush fridge magnet and a keychain. Incidentally, “The Little Mole” was originally created in the Soviet Union. Strangely enough, I seem to have a taste for all things Soviet. In Berlin, my favourite neighbourhoods were the Soviet blocks. A kind of inherited complicity with socialism? I don’t know.

In Prague, conversations with a friend helped me figure out a few things—especially what I really want. (People have been asking me this recently. Is it age?) Finally, I could say to myself: I know what I want, and I want it hard without effort. What I may need is simply a companion—not someone to constantly share emotions with (I honestly don’t feel that many emotions anymore), but someone with whom I can work, build interesting “projects,” and achieve things. Affection or love can only emerge from meaningful interaction and sustained evaluation. Oli told me two months ago that love, if it is to be genuine, must always carry high risk. Still, I must reduce that risk within a controllable range, and strengthen my capacity for self-protection and self-repair. No matter what story unfolds, what I need most is a stable inner state and space for solitude—that’s where my subjectivity truly takes root.

Also, the recent scandals in both academia and the entertainment world have left me stunned. In those fleeting moments of reading the latest headlines, I’ve even felt a trace of sorrow. Humanity, as a collective, seems so pitiable—trapped in its own desires, in the gaze and expectations of others, in the rigid norms of society. And none of this is really within my control. I’m just one of the many pitiful ones. Life is beautiful—but the hardships of living often try to make us forget that.

Still, despite all this, I feel happy. That’s what Prague gave me. In the Old Town Square, I stumbled upon a Salvador Dalí gallery. I decided to go in within a second and asked my friend to wait at the bar downstairs. Dalí has been my favourite artist since 12. He’s the very image of delightful chaos. In his dreamlike paintings, all fixed meanings dissolve. Those are the rare moments in which I can escape from “language.”

One morning at the hotel, my friend asked me why I obsessively arrange all my belongings in order, almost compulsively. I suddenly realized: my sense of subjectivity has, at long last, been restored. Since I was 21—during my exchange semester in Taiwan—I couldn’t sleep unless my desk was perfectly tidy. But after I moved to Belgium, due to a flood of emotional turmoil, I stopped caring about my room. My mind and my mood were chaotic. That interior disorder became external. I remember that semester in Strasbourg, when I couldn’t even bring myself to do the dishes. My thoughts were not with myself; my time was consumed by a story with neither beginning nor end. I never want to feel that way again. My life must be mine.

Fortunately, since last semester, I’ve resumed making my bed, restoring order in my room, caring again about cleanliness and clarity. Back in Belgium, when friends stayed over, I would keep using the same sheets and bedding they had used. But now, I habitually clean everything after someone touches my things—because what is mine must remain mine.

.

A Serious Play

2025-07-23 05:04:45, Germany

Right now, I’m sitting at an Italian restaurant next to the Munich train station, waiting for the overnight bus to Prague. This afternoon, I took a seven-hour train ride from Switzerland to Munich. On the train, I worked intermittently on the paper I’m preparing for the Paris conference in September. I feel genuinely good—finally, the writing has reached a breakthrough. After getting off the train, I even gave myself a little compliment.

Overall, July has been a beautiful month. One thing followed another, yet everything seemed to move forward with a kind of self-sustaining rhythm. Even while traveling, I’ve been able to find time to write and to reflect on small problems as they arise. I now enter a working state much faster than I used to. Once I step off the train, I deliberately set aside those scattered thoughts and let myself immerse fully in the pleasures of the sensory world.

Earlier today, while waiting for the bus, I looked up and saw a large tree. Some of its branches had broken off and healed over with rough knots. Last night, walking home, I noticed rain-speckled leaves—smooth in texture, but lined with serrated edges.

A few days ago, a friend from Leiden came to visit Switzerland, and we went hiking together. On the trail, I kept asking him about Nietzsche’s theories. I’ve been particularly struck by two notions: the “will to power” and the idea of “play.” The last time I read Nietzsche was the summer before I graduated from college. Each day, I’d go to the third floor of the library, sit by the window, and read Beyond Good and Evil. I scribbled notes on nearly every page (which, admittedly, was an act of vandalism against a public book). Most of those notes I no longer remember, but I’m surprised by how deeply Nietzsche has embedded himself into my very way of being.

Nietzsche’s idea of the “will to power” is not about concrete domination—it’s about how one might integrate a diversity of desires into a coherent life. Our lives are fragmented, full of contingencies—yet there seems to be a force that gathers them, brings them back into a kind of unity. Life becomes a game of self-regulation and self-assessment, a game whose rules demand perpetual “self-overcoming.” And if it is a game, it implies both rules (some socially and culturally imposed) and freedom (I have absolute control over how I play, and I can question all given rules without blind submission). But precisely because it is a game, I must also play it with seriousness and rigor—only then does life become truly joyful. Once life begins to self-organize, the very concept of subjectivity becomes both a necessity and a fiction—because in truth, I could become anyone, if I so wished.

Lately, I’ve realized that it took me four years to fully admit to the failure of a past decision on the relationship. But mere acknowledgment is not enough—otherwise, I risk becoming afraid of failing again, which leads to weakness in action and emotional paralysis. Failure itself is not frightening. What matters is that I construct a new kind of protective system after failing—but not one that numbs me or prevents immersion. It should not be an “anti-addiction” mechanism that suppresses my ability to wholeheartedly experience emotional flows. Rather, it should be a system grounded in “possibility”: I must always be able to walk away from any game, yet also be fully willing to participate in it with all of myself.

It’s like when I was searching for a PhD advisor. At first, I stubbornly fixated on the one person I thought was perfect for me—and that left me in a half-year spiral of anxiety. But after I let go of that imagined “uniqueness,” I suddenly reached out to four other outstanding professors. It wasn’t that having more options made me feel secure. Rather, it was the existence of such a defensive structure that allowed me to pursue my goals calmly and steadily.

Looking back on all of this, perhaps the essential task is not how to deal with failure when it happens, but how to pre-acknowledge the possibility of failure and prepare a positive form of defence in advance. Only then can I devote myself entirely—with courage and energy—to the best option I believe in. In that sense, “security” is something I must grant myself. To place hope in another is not only unreliable—it may not be a remedy at all.

My Soul Still Lingers in Reykjavik

2025-07-05 03:36:28 Swiss

A conference brought me to Iceland for a week at the end of June. I have been back in Switzerland for four days now. I have no motivation to study. My soul did not come back with me. It remains among Iceland’s primitive tundra and glaciers.

Ten years ago, I wanted to come to Iceland. It was because of a song called “Reykjavik” by Juno. The lyrics went: “Still I trap myself in empty dreams, the unextinguished passion broadcast for ten years, like a hot spring gushing into a cold ice cellar. In the battle of hot and cold, whoever has patience wins, frozen old love thaws again. (還是 我自困 空想之中,未熄的熱情 用十年來放送,彷彿一眼熱泉 湧進 寒冷冰窖中,炎涼大戰中,誰夠耐性便勝利,冰封舊情再解凍。或者失約 一早已在你 預備中。堅守冰島只是我 未望通。根本不是 天下情人都 求重逢 重溫美夢。情人都 求重逢 重修破洞,如情人都 能重逢,情歌少很多 精彩內容)”

“The unextinguished passion broadcast for ten years.” Ten years ago, I was just starting high school. I never imagined I would actually be in Reykjavik ten years later. On the first day, walking alone past the art museum, I felt supremely happy. I had really come to Reykjavik! This was the first time Iceland saved me. It helped me fulfil an adolescent expectation and let me feel again those years that flowed like a fresh river. It allowed all the unfinished, unrealized regrets to take another form and continue to dwell in my life. This made me feel happy.

The trip to Iceland was too perfect. I don’t know where to begin recording it. On the first day, my friend and I signed up for a day tour to the famous Golden Circle. The bus drove steadily on the highway. Tundra, grassland, glaciers, volcanoes–but always empty of people. Perhaps from that moment, my soul was stuck to this island. Enormous waterfalls cascaded down from patches of green. People are too small, too powerless. But I like this feeling. Hot air rises constantly from the ground everywhere. The earth is alive.

Days two and three, I attended the conference. After my presentation, three friends asked me questions. This was good. During lunch at the conference, I sat with a group of strangers. They were philosophy professors from around the world. My presence at this table was pure chance. But during our conversation, I suddenly realized one of the professors was a teacher for the philosophy summer school I had applied to this year. I chatted with her briefly and learned some inside information about the selection process. After lunch, I found another German professor she mentioned and introduced myself. Though he said the competition was fierce, he had me write my name down for him directly. Yesterday I received an invitation to the summer school. I don’t know if those few minutes of casual conversation made the difference. It felt like I was playing a single-player game, collecting clues from different people, completing tasks, then unlocking new scenes.

On day three, I asked Professor He, who studies the “I Ching”, a question at the conference. During the break, quite by chance, I chatted with his doctoral student. The student was German but spoke good Chinese. He said he was returning to Germany the next day and couldn’t take Professor He, whose English wasn’t good, on a tour. I said, my friend and I are going to Iceland’s south coast tomorrow, why don’t you join us. He agreed.

On the fourth day in Iceland, my friend, Professor He, and I boarded the tour bus together. I’ve always been very interested in the “I Ching”. This was one important reason for my invitation. Another reason was that Professor He, though nearly seventy, was spirited and upright, handsome and quite talkative.

On the road, I chatted with him about fortune-telling. I told him many stories I knew of fortune-telling that was remarkably accurate, even frightening. This was showing off my meager skills before an expert, since Professor He is a famous Feng Shui master in China. After hearing my anecdotes, he was silent for a while. Then he told me he had visited Iceland’s “lava museum” a few days before. The lava there was so realistic that people might think they were surrounded by actual lava. Our sensory world is much like this lava performance. What we see and hear, what we listen to and feel, is not absolutely real. We simply choose to believe it so. Perhaps we will finally discover the world is virtual.

Later we reached another waterfall. On the way back to the bus, he asked if I could explain phenomenology in the simplest way possible. Why “simplest”? Because he said his colleagues’ explanations weren’t very clear to him. I said phenomenology is really about explaining how we touch a cup, how we see an object. I think the “I Ching” or traditional Chinese philosophy might start from grand but accurate “intuition” and reason down to the specific, personal self and life, while phenomenology starts from extremely minute perceptions and reasons out the organizational pattern of all nature, even the universe.–These two paths must meet at the same point. He seemed quite satisfied with my answer. This made me happy too, because I clearly felt my progress. Four or five years ago, I couldn’t have given explanations that convinced both myself and others.

Almost every night in Iceland, I went alone to see local free live music. The first day was punk, the second day I went to the “punk museum,” the fourth day I went to a rock show, then moved to another bar to watch DJ and drum performances, the fifth day I saw the last rock show, leaving before it ended to catch my flight back to Switzerland.

These brilliant performances were the second time Iceland saved me. For the past four years, I had been writing the same story repeatedly, like a compulsive repetition. I was always talking about how I was loved, deceived, abandoned, blamed, and so on. In those years, I had lost interest in many things, including music, which I used to love most. I seemed castrated, having lost interest in and love for the world. These were all self-imposed prisons, but I could only spend those long four years this way. Like cutting out rotting flesh, new flesh needs time to grow and fill the wound.

However, those nights in Iceland formally let me say goodbye to all the past. Like a person with a broken bone finally removing the plaster cast. True freedom and vivid subjectivity returned to my life–undoubtedly a tremendous gift. I thank myself too. Through constant study and writing this year, I had the opportunity to come to Iceland and complete this journey like a farewell ceremony. I also thank myself for being kind to people, allowing me to meet good teachers and friends who led me out of layers of confusion and difficulty.

My strongest feeling in Iceland was “I am happy, I am truly lucky.” At the conference, I asked Professor He a question: Is the historical pattern linear or cyclical? He said many things I can’t quite remember. But he said although the “I Ching” can predict future directions through various historical facts with around 60% accuracy, what keeps us away from “determinism” is the giant “nature”–this is where infinite possibilities lie. During these days, I mysteriously met a Taoist priest online who said he could help me pray for smooth romantic fortune through ritual practices, as it was the largest challenge in my entire life. I hesitated only a few minutes before paying the considerable fee. Funny fact is that I only questioned whether he was a fraud; I never doubted whether the ritual would have its claimed effect.

My recent research topics are “narcissism” and “mirror phenomena,” which have very close logical connections. When I smile at the world, it smiles back at me. When I trust it, it trusts me. I seem to realize that trust exists not only between people, but also between a person and their own fate. When I believe I deserve a better future, I have the courage to walk toward it.

Well, I think it was necessary to write this journal. These days after the trip ended, I was always distracted. Like someone holding their breath, unable to concentrate on work. Writing this journal is like “breathing.” Okay, now, I finally had time to write this journal, so I should be able to continue my work.

Today, on the way to the office, I recalled my first year of doctoral study. There were quite a few achievements: three book articles, two international conferences, two domestic conferences, one journal article, one translation article.

July’s tasks remain heavy: 1. Finish the online course on the “Tao Te Ching” (average two lessons per day; because I want to continue studying the “I Ching” course, I need to accelerate); 2. Finish the paper for the Paris conference by July 14; 3. Begin translating my supervisor’s work in late July; 4. Exercise 20 minutes daily.

Looking Back A Little Bit

2025-06-20 20:03:34 Swiss

1. The Emotion Problem

This is my fifth year in Europe. I have grown “steady.” Last week I was editing a collaborative paper and wanted to curse. When my friend walked over and asked how I was doing, I smiled and said, “I seem very angry right now.”

When I graduated from college, I was the kind of unstable person who would storm into the dean’s office and argue with him because I disagreed with the school’s evaluation policy.

The first step in controlling your emotions should be to quickly recognize what you feel. Then you can pretend nothing happened. Don’t be greedy. Accept whatever life gives you. Allow everything to happen. Whether it’s what you expected or not, recognize your emotions quickly. Control your immediate emotional reactions. Accept reality again, seriously.

But is learning to master emotions lucky or unlucky? That’s another question to think about.

The result is that I handle my suppressed emotions by ten-seconds screaming in the office at night. I sing on the road while cycling at midnight. Then I go home. Everything is calm again. Nothing happened. But sometimes the emotions build up to a certain point and become a good cry. After crying, it seems fine again.

Anyway, peace of mind is the most important thing.

2. The Ranking Problem

Tonight I was smoking secretly by the office window. I suddenly thought about ranking “purity, diversity, and intensity.” (Indeed, another case of inexplicable overthinking.) But I really ranked them: purity > intensity > diversity. Keep everything simple in life; Then you can have high-intensity events; Events solved quickly and well can bring diverse events with intensity. If it were the other way around, it would be the worst. Haha.

Today while writing the paper, I kept thinking about the logical order of trivial matters. (Maybe my OCD was acting up.) I did academic writing while listing the causes and effects. This is probably a benefit of ADHD. Being able to think about several things at once. Maybe it’s a habit I developed from watching TV while doing homework as a child. Fortunately, today I was doing simple text writing. No key concepts to understand.

On the bike ride home today, I found that overthinking might affect action. So recently I started reading and writing some political philosophy again: making decisions and doing acting at the right time. (Good news is that my paper on Carl Schmitt’s political philosophy was accepted by the phenomenology conference a few days ago.)

If it’s not something that requires a decision, should I let them maintain a “quantum superposition state”? Do I actually like this superposition state, or can I not face the consequences of reality “collapsing”?

Also, yesterday I finally admitted my parents are really very good parents (perhaps, the present can modify the past). They never interfere with my decisions. As long as they’re reasonable, they support them. But this might also be because my decisions are all reasonable decisions. Or they are very confident in their education since they think that under their influence, I won’t make outrageous or stupid decisions.

(Except for a period in my sophomore year of high school when I wanted to drop out to study painting as my profession. They objected and analysed the pros and cons with me all night. In the end, I agreed with their reasoning and gave up the idea.)

3. Writing Experience as a Collaboration Problem

Having a personal website is really nice. I don’t have to write journals on websites I don’t like anymore. They don’t have the styles I prefer. I started writing diaries in notebooks in 2016. In 2020, I even brought my diary with me when traveling. Later, because there was too much to record, I simply switched to the internet. A while ago, I flipped through my reading notes from 2017. They were quite touching. Actually, my core hasn’t changed much—this is also a very good thing.

Professionalizing philosophical work might really make people more picky and controlling. Ihave to ensure the accuracy of every sentence. It must also fit my philosophical aesthetics and literary taste. Therefore, sometimes I can’t stand other people’s “messy” arguments. This is especially obvious when collaborating on papers with others. I have to revise every sentence until I’m satisfied.

This also makes me realize the importance of choosing the right teammates. If my colleagues also had control issues, they might not be able to stand my large-scale cuts. Fortunately, they are relatively lazy and didn’t mind my major adjustments. If my teammates had the same “cleanliness obsession” with words as I do, we couldn’t collaborate; If they have an indifferent attitude, although my workload increases significantly, the final result will satisfy me.

(I suddenly noticed that my sentences are getting shorter. Is this also a kind of mental state change?)

4. Academic Activities as an Interpersonal Problem

Yesterday I received an email from the professor. He said he was very satisfied with my editing work and co-authored papers. At the same time, I suddenly realized the benefits of collaborative articles: I could never write such interdisciplinary research papers alone—film theory, experimental psychology, neuroscience, philosophy—perhaps this is also a gift brought by coincidence.

I think back to meeting everyone at summer school last year. We had eight days to get to know 30 students from around the world—undergraduates, masters, PhDs, postdocs—and then form teams freely to write articles together. So this game was not just an academic exchange occasion, but more of a social occasion. How to use your research topic to attract strangers’ interest and make them willing to trust you, work together and discuss.

In the end, I participated in the research of three groups. Besides being good at philosophical argumentation, I also had to be happily open to myself, communicate with people positively and kindly, and finally gain teammates’ trust. On the contrary, I noticed that some people seemed too introverted or too arrogant, so they didn’t even participate in a group or formed their own group. I think this was not a problem with their research ability, but ultimately a character problem.

.

The First Day of Being Twenty-Seven

2025-06-19 21:45:17, Swiss

I’d been planning to build a personal website for months. The site finally went live on my birthday—a gift I’d prepared for myself.

What surprised me was how many friends sent birthday wishes this year, from those I’d known just a few months to those I’d known fifteen years. Some friends I never even remembered telling my birthday. I felt deeply happy and lucky.

I’d been busy lately—chapter articles, conference submissions, paper revisions, translation work. I hadn’t really wanted to celebrate my birthday, but LI invited me to her place. I left in the morning. Google Maps said twenty minutes by bike, but it routed me through the entire forest near my appartment. I pushed my heavy bike through the forest for over half an hour. Just as I emerged onto the road, two or three garbage trucks passed by. The stench and blazing sun nearly made me almost vomit in the roadside grass. I closed my eyes for five minutes, waited for the smell to fade, then continued riding.

I finally reached her place after an hour. We ate udon noodles and a small cake she’d prepared. I saw sparkler candles for the first time. I was really happy. She asked if I felt lonely, constantly traveling abroad. I said I was probably used to it by now. Good friends always stay close in unexpected ways. We talked about “romantic relationships”—she was shocked and disappointed by my years of “hesitation” and “silence.” She said, “Good boys and good girls don’t end up together. That’s why good boys always end up with bad girls, and bad boys always find good girls.”

I went to the office in the afternoon, couldn’t focus on studying, and continued working on the website. I looked through many old photos. I’d been to many places, met many people. That evening, after LI finished her exam, we had dinner together at an Italian restaurant in the old town. I ordered pasta, she ordered pizza. She also bought me a cocktail—mango, passion fruit, orange, and grapefruit flavored. It was really good! After that, she took me wandering around the city, hoping to find a party—a dancing party. I told her I’d never been to a dancing party. She was shocked again. We circled the city and came back empty-handed. I said goodbye to her at the bus stop at eleven-thirty.

On the bike ride home, I heard someone calling my name. It was Al and Ya, two friends I’d met about a month ago. I told them it was my birthday, and they congratulated me. I told them my friend and I had just searched the city for a long time without finding a party. Al said they’d just returned from a student party. After some conversation, Al and I went to a lively end-of-term celebration party. I rode his electric bike. Electric bikes are nice—I thought I could save money to buy one in the coming months. Though we went to the party, we sat on a bench under a big tree away from the crowd. He started talking about some romantic confusion. Being young is good. While trying to understand him, I also remembered many people and things I’d encountered over the years.

But, I suddenly found a reason for my “silence” and “inaction”—I needed to feel “safe”! So, very fortunately, in the first hour of the first day of my birthday, through this accidental encounter and conversation, I forgave my apparent “incompetence.” First, being alone in various European countries (Belgium, France, Switzerland, Netherlands) wasn’t easy. The feeling of drifting didn’t always mean freedom and liberation—it basically meant I needed to be stronger and even more independent.

Second, I’d already been hurt once, by one of the people I’d trusted most. I had good reason to protect my sincerity more carefully. I couldn’t help being afraid of commitment—both others’ commitments and my own. If I committed, I would definitely work to build a future, but were others’ commitments reliable? Were they people who could make commitments and not betray them? These were things I had to consider. Of course, I couldn’t keep being afraid forever. Being capable of hurt only means our hearts could still feel “love” and still expect “love.” Like the sentence that suddenly came out when I was talking with Al: “bad things are only the appearance of good things.”

People should know what they want. For me now, I suppose, many things require the quality of “loyalty”—to oneself, to others, to career. Over a year ago, in the acceptance letter my advisor sent me, he asked me again whether I was willing to give my research a “commitment.” I emailed back: “Absolutely!” I hadn’t realized then that this commitment would become an important motivation for my persistent studying and writing this past year. I’m not wildly ambitious—I’m just responsible for the path and career I’ve chosen. Isn’t this the quality all good relationships need?

I’m not sure if such thinking is too serious. But I think we and the world are like mirrors facing each other—we smile at it, and it smiles back at us. We treat every person and relationship seriously, and they treat us seriously in return. In this seemingly convenient age, everything—eating, dating, marriage, healing—seems to be fast-forwarded. But what remains in life’s long river are only the heavy, stubborn, enormous stones. Of course, the years will leave us deep love, if we are a great river and not a small stream.

.

Missing a Band’s Singer

2024-01-20 10:19:36, France

It’s been a long time since I heard news of them. They were long entangled with my boring college years. And now I’ve completely bid farewell to my college time, because I also seem to have gradually emerged from those days of genuine heartbreak and bankruptcy. Inexplicably, I now suddenly and especially miss those days of loving those reckless lyrics:

“Can you be the scar I wake up with after drinking / not knowing where it came from / just consider it a jasmine flower / blooming in our wasted time / Can you be the cartoon I can’t bear to turn off / before dawn / even if I can’t watch you all night / you don’t have to worry about becoming boring / Can you be / just be everything all / all all all everything everything everything all / all those unknown truths / only by giving up the pursuit can you see them / What a beautiful jasmine flower / fragrant and beautiful covering the branches”

How beautiful this song is.

.

Ordinary World/Nothing Matters

The ordinary world only needs me to wholeheartedly do one common job, nothing more. And what I want must be obtained. I must be responsible for this work, with a sense of responsibility, not just for happiness. This is my promise to myself. I must take this difficult thing seriously because this thing is worth my pursuit. It will not only profoundly change myself but also affect others. This contribution might possibly belong ultimately to humanity’s cultural river, to my friends and descendants. Even if it’s just that almost negligible wave, I’m willing to contribute most of my time and constantly running mind for this tiny ripple. This is a new era that needs new enlightenment. And I am merely one of the megaphones among the ruins of the past calling for fresh life. In this era of rapid progress, I think it’s necessary to look back at the dust in history, in order to continue forward with ancient vitality, to continue proliferating.

.

Two Become One/The Taste of Combination

2023-02-09 02:41:46 Belgium

Today I tied my hair up for the first time in a long while, just like every day before sophomore year, when I hadn’t yet cut off my long hair. Looking at myself in the mirror, I felt somewhat dazed. The way I look now isn’t much different from high school, except my hair is dyed deep red and slightly curled. I do look much more spirited overall. Actually, my mom’s advice was always right—this hairstyle suits me best.

I started teaching myself French today. I need to learn a semester’s worth of content in nine days to take the exam in the first week of school. The plan is three days to memorize vocabulary, three days to go through grammar, and the last three days to review and do practice problems. I can only charge ahead. In the past two years, I’ve intermittently studied some basic content. Though these nine days are very short, it’s not impossible to pass the exam smoothly. Either way, I have to study.

Today, during a study break, the moment I returned to my dorm after smoking on the balcony, I suddenly smelled the scent that permeated my parents’ office when I was little. Cigarette smoke mixed with the smell of leather furniture. As a child, I didn’t like this smell. I never expected I would become a producer of this scent. Perhaps this is adult compromise. Needing to rely on the momentary relaxation that cigarettes bring to overcome the hardship and complexity of the present time, needing soft black leather chairs to comfort a spine bent over desks for long periods. Facing life’s uncertainties, I need to push a stone of my own choosing up a mountain day and night, not knowing where the end lies. This anxiety was too difficult for my childhood self to understand, let alone experience.

While smoking on the balcony today, I looked at the trees outside the window. I suddenly felt that some people are like trees—rooting in one piece of soil, then slowly growing, habitually beginning to occupy the familiar territory beneath their feet. Others are like schools of fish in the sea, needing to migrate everywhere, whether due to the passive necessity of ocean currents or the active contingency of seeking food—they’re always experiencing different scenery. I should belong to the former. On one hand, it’s the nature of laziness and fatigue; on the other, it’s the ambition of stubbornness and persistence.

.

Cigarettes on the Balcony

2022-09-25 04:20:58 Belgium

The weather is getting colder and darker earlier. Recently I’ve been in the habit of smoking on the balcony after meals, two to three cigarettes a day. I started smoking at the beginning of the year, at a New Year’s gathering where a friend rolled my first cigarette. Afterwards I found rolling cigarettes enjoyable, so I spent less than ten euros on a smoking kit: foam filters, rice paper, and a pack of tobacco. At first I couldn’t inhale properly at all—as soon as I drew it into my body, I would cough uncontrollably. After about a quarter of a year, I gradually became familiar with that dizziness and stimulation, stopped coughing, and the degree of lightheadedness also lessened. As for why I wanted to learn to smoke, I don’t know. Probably to draw a clear line from my past self. To commemorate the self-consumption approaching death and emotions constantly driving toward decay—besides smoking, I also got a tattoo. I don’t know why I couldn’t imbue that pattern with meaning in what seemed like such a strongly symbolic event. Perhaps its meaning was too manifold, carrying too much of my imagination, desire, and sentimentality. It remains on my arm while maintaining a distant relationship with me.

Smoking on the balcony, sometimes the birdsong is very loud. Gazing at distant trees, yet I can’t see a single bird’s shadow. Where does such loud sound come from? Is everything just my hallucination? Of course not, I tell myself with a laugh.

This year has really passed so quickly. I remember receiving a friend’s call in early October—he said it was raining where he was, and I said what a coincidence, it’s raining here too. Two years ago now, I was preparing my doctoral application; two years later today, I’m starting to prepare doctoral applications again. But what I want to do, the topics that interest me, have changed dramatically. In these two years, the only thing worth being proud of is that I’ve really been seriously experiencing everything life brings me. Two years ago, I seemed to face the complex world with a blank slate mentality. Back then I wasn’t afraid—I would directly do whatever I wanted without hesitation. But now I know fear, know that many things aren’t so simple and plain. Therefore I can no longer speak and live so recklessly. And someone told me this is absolutely not cowardice, but requires greater courage—requires re-engaging with life in a self-aware and self-controlled posture. Living seriously.

As my last cigarette of the day was ending, I said to myself: “My life can’t be on autopilot anymore.” My life and I still maintain a difficult-to-bridge distance—I don’t naturally possess selfhood. I need to be responsible for it.

.

Flowers Bloom on the Shore/Bye Bye Almost Summer

2022-08-03 00:57:36 Belgium

Half the summer has passed like this. Everything gradually returns to a normal state, living peacefully day by day. Some people have changed from friends to strangers, others from strangers to friends. There are departures of the most familiar people, and also lingering traces of weak/most distant nostalgia.

Sometimes I can’t distinguish certain relationships, or rather I’m always unwilling to clarify them. Perhaps only my thesis needs to be neat and regulated—daily life doesn’t need the rule of concepts, nor is it driven forward by concepts.

Debussy lets melodies flow in the air, like moonlight spilling onto the sea surface, stirring up shimmering ripples. I think I can be more open, allowing everything to happen within a place, rather than being a container bearing weight.

Recently I like watching people in exaggerated makeup, similar to theatrical effects. Terayama Shuji’s gorgeous/poignant shots make my heart race. Those colorful eyeliner, bright blush, huge red lips, pale faces—all these can be possessed by ordinary people!

Why don’t people want beauty anymore? Why has beauty become the source of sin? Why has asceticism become part of consumerism, consuming people’s love for color, praise for flowers, rejection of azure/fresh green/bright red/… to the utmost?

Should a man who loves beauty exist? Or should he naturally exist? Loving beauty can be women’s nature—why can’t it be men’s? If men can’t learn to truly possess beauty, then isn’t their appreciation of beauty utilitarian and instrumental?

But even if women have the most natural pursuit of beauty, how can their pursuit of beauty not be eroded by functionality? When their beauty depends on certain value judgments, their utmost efforts are merely requests to share a piece of the pie. The discipline of women’s love of beauty has always been strangely pervasive throughout consumer society.